The Art of Storytelling – The Ugly Duckling

Music from Wyastone – Studio Concert Series

Want to view the full video?

You need to be an ESO Digital Supporter to view the full content. Please click here for more information, or sign in to your account below if you’re already registered.

Already a supporter? Click here to log in.

Programme

Kenneth Woods The Ugly Duckling

Artists

English Symphony Orchestra

Conductor: Kenneth Woods

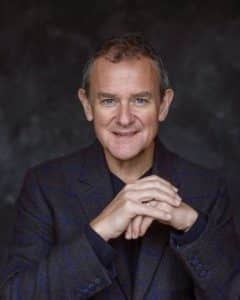

Narrator: Hugh Bonneville

Illustrator: Wanda Sobieska

About this Concert

When an aging Hans Christian Andersen was asked “why have you not written an autobiography?” he answered simply, “I have. It is called The Ugly Duckling.” Andersen’s children’s novella is one of the great literary works of the 19th Century, a masterpiece which embraces the whole of the human journey through life from the most agonising moments of rejection and self-loathing to the euphoria of true self-acceptance. Listeners who have grown up with the charming song sung by Danny Kaye in the 1950’s Andersen biopic may be surprised to learn that Andersen’s story is different in dozens of ways, right down to the colour of the Duckling’s feathers, which are, in fact, grey rather than “stubby and brown.”

A new musical setting of Hans Christian Andersen’s masterpiece by Kenneth Woods is narrated by Hugh Bonneville, star of Downton Abbey, the Paddington films and W1A. Beautiful and evocative illustrations by Polish-American artist and musician, Wanda Sobieska, brings an additional level of emotion to this poignant melding of music, word and image.

ESO’s ‘Art of Storytelling’ project presents world premiere recordings and broadcasts of five exceptional works for narrator and orchestra. From the cheeky humour of the Brothers’ Grimm to the touching tale of Hans Christian Andersen’s Ugly Duckling, and from the Jewish humour of Lubin from Chelm to the ancient Egyptian tale of The Warrior Violinist, this is classic family entertainment for the modern age at its finest, a powerful synthesis of great literature and great music.

Discover More

About the Narrator - Hugh Bonneville

Hugh Bonneville

About the Illustrator - Wanda Sobieska

Wanda Sobieska is a violinist based in northeast Ohio, active as a solo, chamber, and orchestral musician. Her engagements include work for traditional concert settings, opera and musical theater pits, film scoring stages, church services, private events, and new music concert series, among others.

She is also a prolific arranger: her website, freegigmusic.com, has served musicians since 2009 and receives 1000 visitors a day from all over the world. Additionally, she is proficient as a composer and violist, and dedicated nearly a decade to directing a handbell choir.

Born in Warsaw, Poland, she is the fifth generation in a family of musicians and musicologists. She holds a B.M. in violin performance from the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music.

About the Composer - Kenneth Woods

Kenneth Woods

THE UGLY DUCKLING – A LETTER FROM WANDA SOBIESKA

Dear ESO friends and listeners-

I had asked Wanda to write a blog post about her wonderful illustrations for The Ugly Duckling in advance of this week’s premiere. She chose to do so in the form of this beautiful letter, which I am very happy to be able to share with you all.

— Ken

Kenneth Woods – Artistic Director

Wanda and Ken with conductor Bradley Thachuk at the Canadian premiere of The Ugly Duckling with the Niagara Symphony Orchestra in 2018

Hello Ken,

For some reason, I found it easier to present my thoughts in the form of a letter. I hope you find some meaning in there.

I am copying and pasting below.

===============

November 23, 2020

Kent, Ohio

Dear Ken,

I can hardly believe that it has been five years already since the initial premiere of our “Ugly Duckling”. How time flies!

I write this letter at a curious moment in time: both looking forward to the upcoming performance with Hugh Bonneville and looking back over the initial process and the duckling’s many simple and sincere steps over the years. It feels like a moment that is a mirror, both looking into the future and reflecting the past.

I remember the very first illustration that I conceived for “The Ugly Duckling”. It was a picture of nothing at all. Literally, it was the blank white slide that is presented as the narrator relates the details of the duckling’s harrowing struggle to survive the winter.

The reason it is blank is because there is no music at that moment. When I first started to work on the project, I decided that what lay at the heart of it for me was not what I could create but how well I could listen. So I burned a CD with the audio track that you had sent, plopped it into the appropriate drive in my trusty 2003 Dodge Intrepid, and burned the tires off driving all over northeast Ohio while immersing myself in the text, the plot, and most of all the music of that recording.

My younger brother and sister used to joke that my beloved car of that era was like the Tardis: dark blue, capable of traveling at warp speeds through the space-time continuum, and bigger on the inside than on the outside. I found the Duckling to be equally magical.

And so I listened: sixty, eighty, one hundred times? I couldn’t really tell you how many. But I can tell you that I listened as many times as was necessary for the work to reach a sort of saturation point in my soul: a point where I had not only memorized it, but at which it had become internalized into the very reflexes of my being. And at that point, out of the haziness of some general outline appeared the blank white slide paired off with the struggles of winter.

The Duckling in the depths of winter

It falls at the lowest point of the story: the moment of complete hopelessness, greatest tragedy, and utter despair. When I listened, I heard a moment of such heart-wrenching grief that the music could not bear the task of accompanying it. And if the music could not support it, neither could my illustrations: they were so tied to your score. So I left that spot to speak for itself.

In a curious sort of inversion, the same effect is in use at the very beginning: the narrator speaks the opening line on a blank black slide. Then the first image fades in together with the music. As at the moment of greatest tragedy, the absence of music spells a dramatic death, so at the opening of the story, the music conjures in the illustrations because it is the source of life.

Before the music conjures life, there is nothing.

That blank black slide is in a sense echoed throughout the story in the occasional illustrations that rely on silhouetted characters against a colored background. And their polar opposites appear at the very end in the white shapes of the swans. After all, the most magnificent transfiguration can only be possible if sourced from the depths of despair.

Silhouettes

ON THE FOUR SEASONS

The blank white slide is significant for another reason. Symbolically, it represents the absence of music, life, and hope. But on a physical level, it depicts snow, and that physical level is very real. It is perhaps the most distilled portrayal of a progression that seemed to accompany and complement the storyline proper as I listened: that of the four seasons.

Translated into more metaphysical terms, this is the progression of life, decay, death, and rebirth.

I found that with the coming of springtime and rebirth, the illustrations took on a more symbolic form. There was a very practical reason for this: at that point in the story, the duckling is already a swan, but I could not show him as such because it would spoil the dramatic effect.

But perhaps more importantly, I feel that this decision is justified in an aesthetic sense. Over the course of summer, autumn, and winter, all the basic building blocks of the story are put into place. With the arrival of springtime, that initial state is essentially reborn, but at a higher vibration. Since the audience at this point would be well-versed in the setting of the story and its key players, I felt compelled to augment this reality at a sort of higher frequency of existence through the use of the symbolic imagination. It is a mode of not only delivering to the audience what is expected but inviting them to openly participate in the process of creation.

That mode, of course, is likewise employed at the aforementioned moments with blank slides and silhouettes, be they black or white. I also occasionally found myself inserting it into other illustrations by way of color, or rather an indeterminate form thereof. The illustrations were all drawn by hand, with graphic software used only for the simplest of purposes: the superimposition of character drawings over backgrounds and the incidental solid fill. As I worked my way through the pictures, I would by and by stop and reach for two very specific art markers. One was labeled “slate” and the other “shale”. The color of those nibs is truly not something that can be described: they are both a curious admixture with varying degrees of gray, brown, purple, and “je ne sais quoi”.

In the illustrations, they appear — one or both — in sporadic spots: tree bark, mountain slopes, shrubbery, fence posts, dirt. My goal, in those places, was not to devalue the importance of that subject matter but, rather than spelling out every detail, to leave certain bits of terrain somewhat “open” and to trust in the intelligence of the audience to imagine and to complete.

ON BOUNDARIES

This approach questions the boundary between the artist and the audience and who it is that actually creates the work of art.

It is but one of the boundaries that I found myself questioning while working on “The Ugly Duckling”.

I wrote earlier that to me the storyline follows the sequence of the four seasons. In terms of this connected flow and the nature of your musical score, the whole forms one coherent unit. However, for me to wrap my mind around the project while at work, I found it necessary to subdivide it into scenes that could then fit back into that overarching unity. I suppose this ventures into the territory of what Samuel Taylor Coleridge termed as “distinguish but not divide”.

At any rate, while this involved a number of components and subcomponents, the biggest distinction for me exists between what I think of as the two “Acts” of the drama, the first consisting of summer; with autumn, winter, and spring comprising the second. The first act deals with the external world: the circumstances into which the duckling is brought. This is reflected by the general “business” of the pictures: the number of characters, the variety of backgrounds, and so forth.

In the second act, the focus shifts to the internal, immaterial realm. In a practical sense, there are far fewer “ingredients” in the pictures and a progression, as I wrote before, toward symbolism. The color purple, which has a somewhat mystical quality, predominates in many shades. And in the final autumnal slide, we see the night sky studded with stars. Among them is planted the constellation of the swan: headed downwards, it is setting at that time of year.

Cygnus the swan in the night sky

The celestial spheres serve as the abode of the spirits; and this internal world is the place of ultimate transformation.

Where does this story truly take place?

Another distinction that I found myself reconsidering was that of foreground and background. While in the beginning, the two are very clearly delineated, this state grew more hazy for me as the entire world of the duckling grew more magical. The whole affair comes to a head at the close of the first act with the illustration of the scarecrow, which (who?) at first appears to be a simple background picture but upon closer inspection proves to be the embodiment of the surroundings on the whole, saturated with a highly sceptical attitude toward our protagonist.

The inanimate becomes animate, and in a not very nice way. The setting can speak for the story just as much as the characters can.

ON A PERSONAL NOTE

On a personal note, not of my own, but of Hans Christian Andersen, a critic apparently once asked him, “Will you write an autobiography?” to which Andersen replied, “I already have: it is ‘The Ugly Duckling’.”

The seeds of the duckling’s magical transformation are present throughout the story. In terms of his appearance, what seems to be an ungraceful hump on his back unfurls into a long, noble neck; and the two black warts on his face turn out to be the handsome black knob above the beak that mute swans so proudly wear. And in terms of the setting, the purple hues of the first two illustrations foreshadow the mystical nature of the second act.

Purple foreshadowings

We know how the story of “The Ugly Duckling” concludes, but this makes me wonder: how many duckling tales are happening in the world as we speak? When one knows the ending of a story, it is easy to look back on it; but when embroiled in the midst of the action, that perspective may be beyond our grasp. I suppose this ties back to my thoughts that opened this letter, and how, in the present moment, I very distinctly sense both the future and the past.

The story of “The Ugly Duckling” is one of those rare masterpieces that speaks to humanity on a universal level. That potential for transformation exists in each and every one of us, and can — and will — transfigure the world into a better place.

With best wishes as always,

Wanda

About Musical Storytelling: Zoë Beyers in conversation with David Yang and Kenneth Woods

ESO Leader Zoë Beyers talks to Kenneth Woods and David Yang about the evolution of the Auricolae Music and Storytelling project which gave birth to many of the the storytelling works featured in our series.

The Music Room series is produced by Shropshire Music Trust and supported by Arts Council England.

Production Information

Recorded at Wyastone Concert Hall, Monmouth, on 31st July 2020

Orchestra Sessions

Orchestra Manager: Simon Brittlebank / The Music Agency

Stage Manager: Ed Hayes / The Music Agency

Producer & Editor: Tim Burton

Engineer & Editor: Matthew Swan

Voice-over Sessions

Producer & Editor: Tim Burton

Engineer: Richard Cottle